Note from SA Charter Moms: We are proud to share guest posts from hallmonitor covering San Antonio’s public schools.

![[Hall Monitor] Texas School Finance Commission: Rough Equity | San Antonio Charter Moms](https://sachartermoms.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/WilliamBTravisBuildingAustinTexas-1024x768.jpg)

Note from Hall Monitor: The Texas School Finance Commission meets for the third time on Thursday, February 22 to hear from more experts on how to to improve the state’s infamous school funding system. You can and should watch. Below are my notes from the first meeting on January 23. The second meeting was on February 8.

People who would like to see school finance reform know two things about the Governor Greg Abbott’s 2017 commission to study the issue.

First, it is Texas’ only active chance of seeing changes made to the universally reviled funding system currently in place.

Second, it’s a slim, slim chance.

During the last legislative session, the passing of House Bill 21 created the Texas Commission on School Finance after the Texas Supreme Court passed the school finance overhaul ball to lawmakers. By declaring the current system constitutional in 2016, “the court has all but closed the door on future court interference,” former associate Texas Supreme Court Justice Craig Enoch said in his testimony before the commission on January 23. The court will likely give “high deference” to whatever the Legislative designs.

The court would override a new system only if it failed to achieve “rough equity” between districts, Enoch said. But short of that, Enoch explained, the lege has a ton of wiggle room.

Furthermore, Enoch said, there is no reason that education funding needs to be tied to property taxes, as it currently is. The commission is free to “think outside the box,” he said.

There’s a lot of freedom, and a full toolbox for the 13-person commission, which will take its recommendation to the legislature by December 31 in preparation for next year’s session.

So why the pessimism? They have the power, the time, the flexibility, the data.

The commission met for the first time on January 23 in Austin, and by the end it was clear why the chance of reform is so slim: it will require the Legislature to admit that not only does poverty matter, but that something can be done about it.

“I want you to understand,” Enoch said, “scholars and educational experts disagree on whether there is a demonstrable correlation between educational expenditures and student outcomes.”

Immediately Chandra Villanueva, a senior analyst at the progressive Center for Public Policy Priorities, tweeted: “Show me a low cost alternative to a high quality teacher or small class size and I’ll start to consider that money in education doesn’t make a difference.”

Of course, neither Enoch, nor anyone else on the dais saw that tweet in the moment.

Equal outcomes should guide the school finance system, Enoch argued, not equal funding. Rather than ensuring that every district get the same amount of money, the Legislature should ensure that each district has what it needs to reach the desired outcomes, he said.

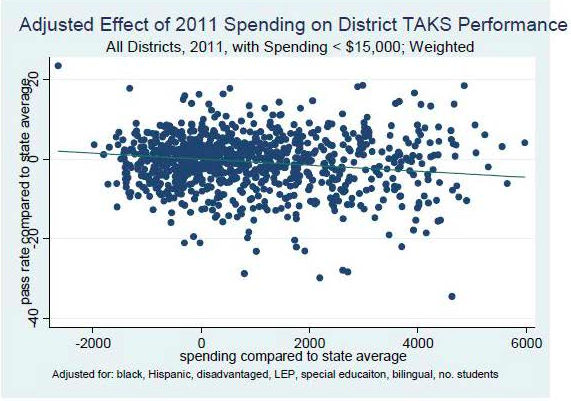

He went on to present a graph that showed districts spending very little money, but performing very well, while other spend plenty of money and performed poorly.

Enoch’s graph presented to Texas School Finance Commission

“There is a pattern here, but it’s not finance,” Enoch said.

This is a trend in the Legislature, commission member Rep. Diego Bernal (D-San Antonio) told me. “There’s a will to prove that there’s already enough money and that it’s inefficient spending that’s the problem.”

Pflugerville ISD superintendent Doug Killian, a commission member, asked Enoch if the spending estimates on his chart included transportation costs, new facilities costs, and other costs that some districts include and some do not include when calculating per pupil expenditures.

“I don’t have an answer to your questions,” Enoch acknowledged; the variables in accounting made it very difficult to compare district expenditures. He also clarified that he wasn’t saying money didn’t matter. “The experts are saying that it’s dangerous to say that only money matters in the education system.”

His graph, he insisted, demonstrated that.

“The devil is in the details,” Killian said, warning that such data might lead the commission to an erroneous conclusion.

Enoch acknowledged that he could not guarantee that the data was consistent, but stood by the conclusion that spending does not determine outcomes. He called on the TEA to determine what really makes a difference.

Texas Education Commissioner Mike Morath, the third presenter of the day, already had the answer.

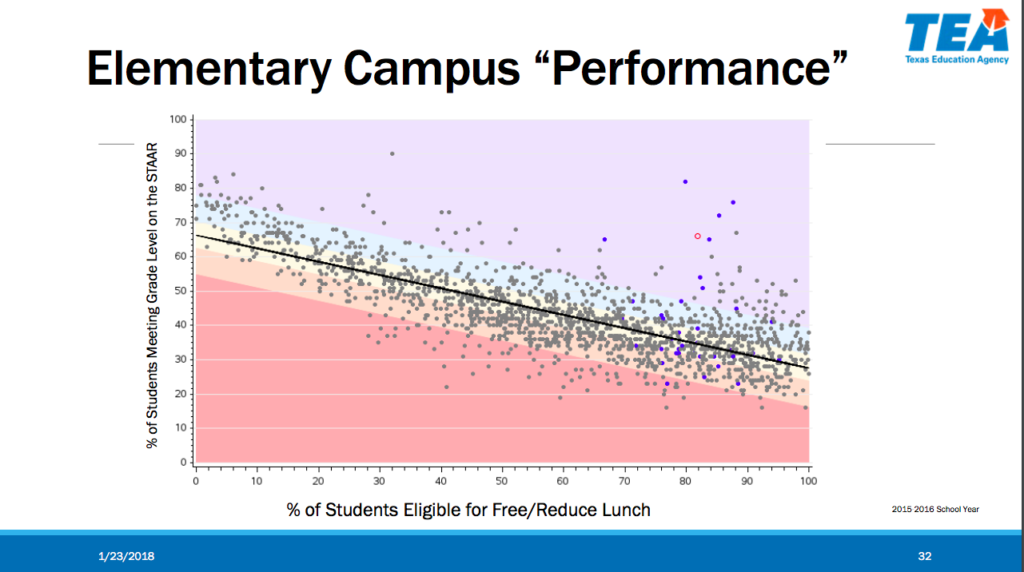

Morath’s own graphs show a correlation between student poverty and student performance. Wealth makes the difference— not how much a district spends, but how much a family has.

From TEA Commissioner Mike Morath’s presentation to the Texas School Finance Commission

Morath’s presentation seemed to support the money-doesn’t-matter narrative, in a way. “It’s not as simple as dollars in a budget functional area,” Morath’s presentation read. “Instead it is programmatic choices and execution quality of that spending that matter the most.”

Texas is among the lowest ten states in the country for per pupil spending. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Massachusetts, which scores near the top of most education rankings, spends $14,515 per pupil (average). Texas spends $8,299 (average).

The lawmakers on the commission offered plenty of alternative explanations for that dubious distinction. Perhaps it has to do with economies of scale, commission member Sen. Larry Taylor (R-Friendswood) said. Texas educates five times the number of students Massachusetts (number one in spending and outcomes) does, and yet both are run by one central administration.

Or perhaps, commission member Rep. Dan Huberty (R-Humble) suggested, Texas spends less because the cost of living here is less than in Massachusetts.

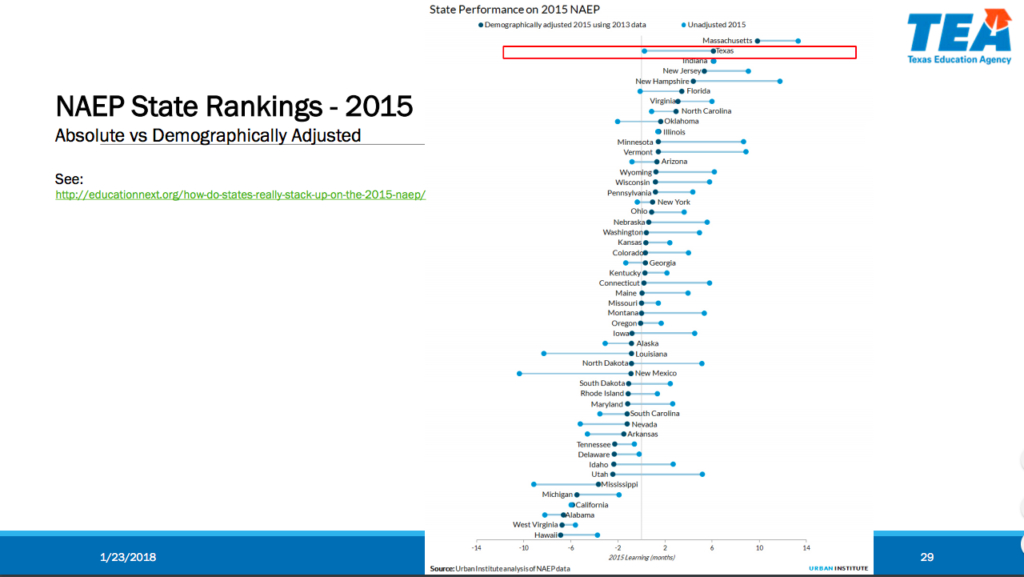

Morath took Huberty’s and Taylor’s points in stride. Whatever the reason, the low spending per pupil did not squelch the quality of education students were getting. When the various demographic subgroups are broken out, and when the scores are adjusted for economic disadvantage, Texas scores near the top on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) test, the gold standard of standardized tests. Texas does a better job educating Hispanic, black, and economically disadvantaged populations than most other states.

From Morath’s presentation to the Texas School Finance Commission

With low per pupil spending!

But don’t look away just yet, Morath warned, because life does not adjust for poverty. Employers don’t ask what resources you had at home, or how often you moved, he explained.

The data shows that in college readiness, graduation, and subsequent lifetime income, economically disadvantaged kids do not outperform their middle class and wealthy peers—not in Texas, not anywhere.

“I’m less concerned with Massachusetts,” Bernal said after the meeting. “We heard today that our students are increasingly unprepared for life after high school.”

It’s not enough to move kids forward, Morath said, they have to reach proficiency. Even though one student is running with crutches, and one student is running with optimum health, both students have to run the race, he said, speaking in metaphor.

When the scores are taken all together and not adjusted for poverty, Texas falls near the middle on performance. Our economically disadvantaged kids do better than other states’ economically disadvantaged kids. We just have more of them.

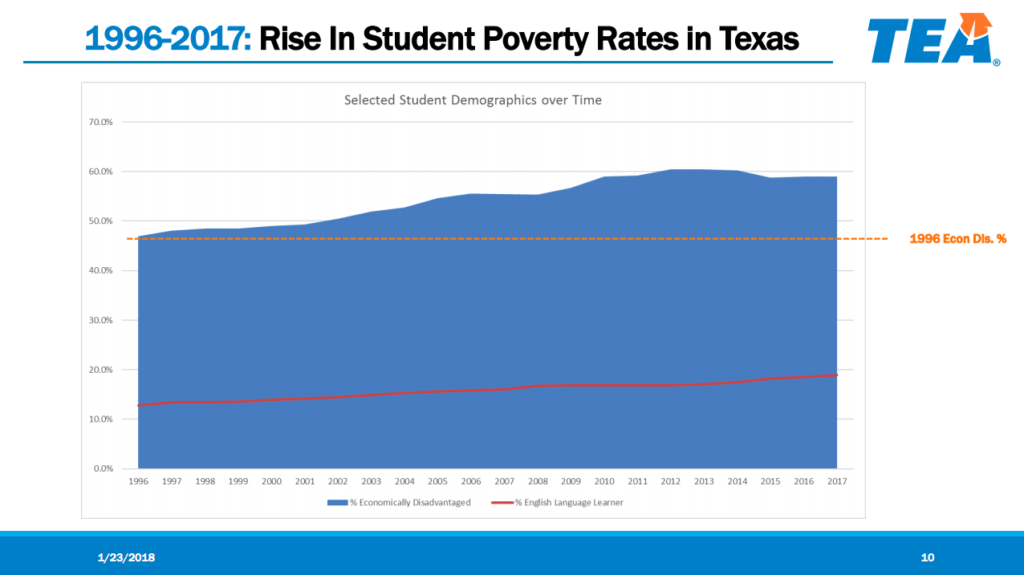

From Morath’s presentation to the Texas School Finance Commission

Since 1996, the percentage of Texas students considered economically disadvantaged has grown, said Morath.

Morath made recommendations with this reality in mind. He agreed with Enoch that big budget numbers were not the key indicator, but went on to show that targeted spending in certain areas with proven efficacy for all students, including those living in poverty: teacher quality summer learning opportunities, and “coherent curriculum.”

Commission member Sen. Royce West (D-Dallas), indicated that the commission might consider different funding streams to support students in poverty, such as health and human services funding. Morath added to that they might consider ways to incentivize spending in certain areas so that money, wherever it might come from, is spent in ways that have been proven to best support those populations.

For example, Morath said, we know attendance improves student outcomes, and so it’s helpful that out current finance system uses daily attendance to allocate funds. Morath would like to see more of these kinds of mechanisms. One idea he floated: higher pay for the most effective teachers at high-need campuses.

Herein, Enoch’s proposition might be more expensive than the current system. Forgetting the arbitrary per student allotments assigned by past Legislatures, if Texas studied what it would cost to close the gap between economically disadvantaged kids and their wealthier peers, we may be paying more than we are now. If we paid for the programs, services, and supports that allowed economically disadvantaged kids to test like wealthy kids, how much would that cost? The commission has the power to ask.

But first, what is the real root cause of low performance, Commission member Sen. Paul Bettencourt (R-Houston), asked. Is it really poverty? Or is it not speaking English as a first language? Is it high mobility rates?

“The thing that matters is poverty,” Morath said, leaving no room for doubt, “Everything else is a proxy for that.”

To be continued . . .

Originally published as “Texas School Finance Commission: Rough Equity,” Hall Monitor, February 21, 2018

Previous guest post: [Hall Monitor] Rumblings Continue in the Battle over SAISD-Charter Partnership

![[Hall Monitor] Texas School Finance Commission | San Antonio Charter Moms [Hall Monitor] Texas School Finance Commission | San Antonio Charter Moms](https://sachartermoms.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/WilliamBTravisBuildingAustinTexas.jpg)