Note from SA Charter Moms: We are proud to share guest posts from hallmonitor covering San Antonio’s public schools.

I’m about 30 years late to the phonics wars, but apparently there’s still plenty to discuss. In my last post on literacy and curriculum, I was having brain-melt over the lack of phonics instruction in schools.

Balanced literacy, critics told me (or I read), was just phonics-less whole language and everything is terrible.

Meanwhile, my daughter’s emergency summer reading adventure is off and running with “sneaky e” and “two vowels go out walking” and all that good stuff.

This has turned our house into a delightful scavenger hunt for long vowel sounds, and my daughter will explain to you that some letters (vowels) are exciting rule breakers and others (consonants) are “boring.” (Not what I thought she’d take from that lesson.) And like every parent whose child is thriving, I assumed I’ve found the literacy panacea.

Not so fast, says Debbie Diller, an educator and author who specializes in literacy. “She’s one of the lucky ones.”

Aha.

Diller was in town offering professional development for elementary school teachers through Pre-K 4 SA. Part of the mandate of our city’s pre-k program is that it offer professional development for the entire pre-k-3rd grade pipeline to make sure that kids get to third grade with a strong foundation.

Pre-K 4 SA brings in literacy experts like Diller to offer the kind of continued learning opportunities teachers might not have access to through their districts. Diller’s June 19 workshop was for K-3rd grade teachers.

“Professional development is key to teaching,” said Pre-K 4 SA CEO Sarah Baray. Teachers don’t just need great preparation programs, they need continued support.

In fact, Diller and Baray both pointed out, the lack of professional development is part of what fueled the phonics wars.

The tendency is to take an approach, or a curriculum, pass it to the teachers and let them implement to the best of their ability. “We do it on the cheap, so teachers don’t get the full understanding,” she explained.

Unfortunately, with things like reading, Baray said, no one curriculum is going to train teachers on the skills they need to use it most effectively and understanding the complexities of literacy development is critical.

“We keep trying to make teaching something you can do right out of the box,” Baray said. “That’s just not the case.”

So then we have phonics flash cards or word-walls without the whole suite of tools, and none of it seems to be working as it should.

In the case of balanced literacy, Diller explained, teachers have to be able to do many things at once—including phonics instruction. (She did join the chorus who agreed that forsaking phonics altogether is educational malpractice, but didn’t say how common it was to see phonics-less teaching.) But it doesn’t stop there, she said. “Phonics is a piece of reading. It’s not the entire puzzle.”

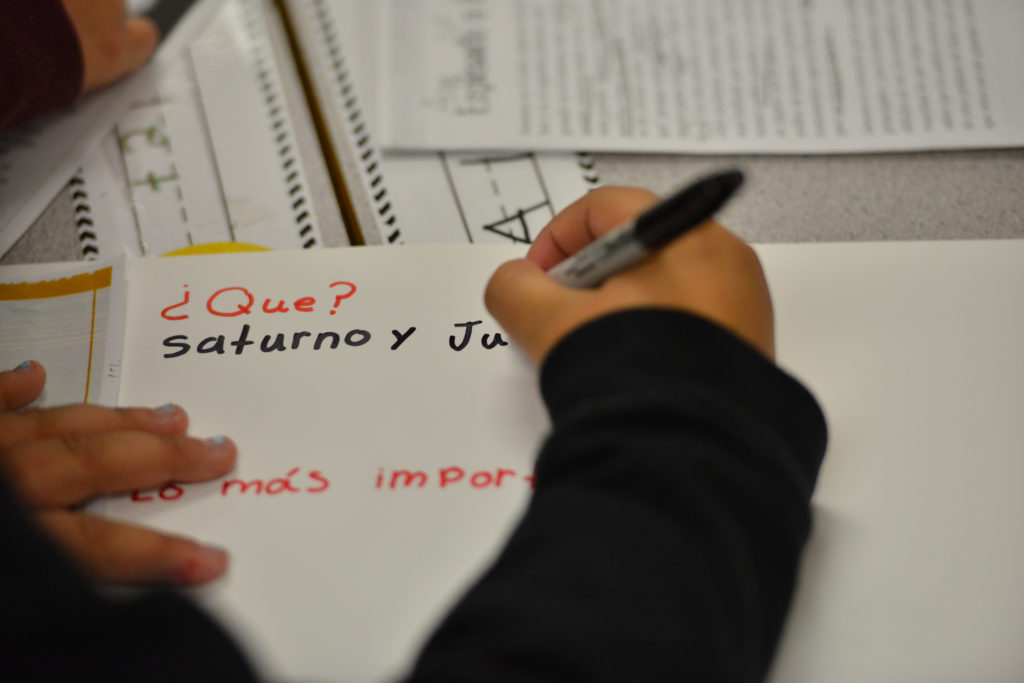

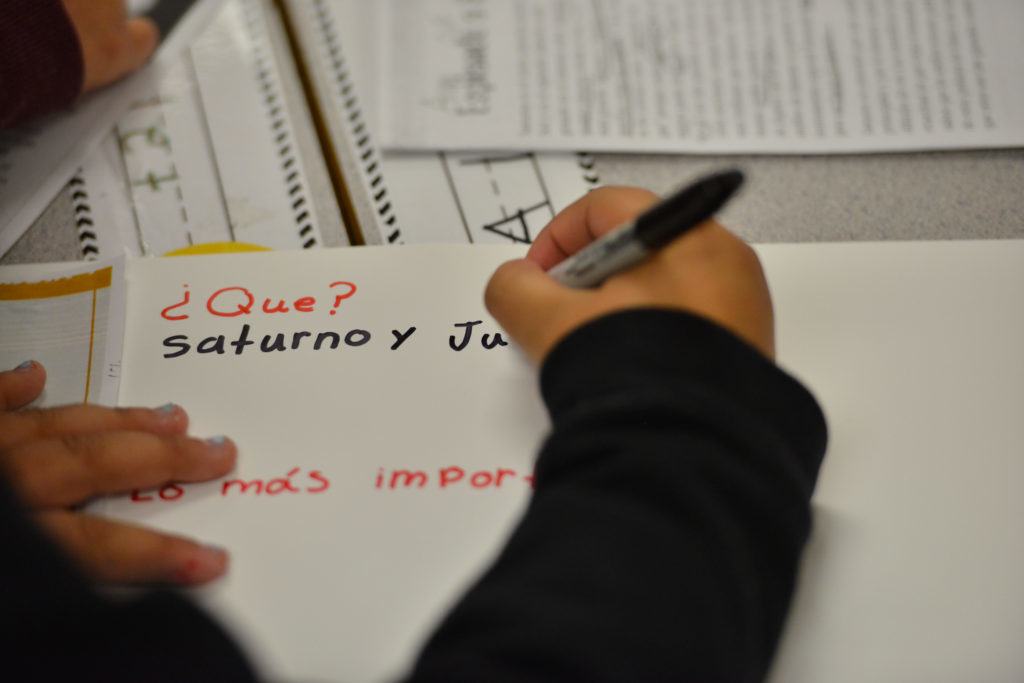

Teaching kids to read is a dialogue, and balanced literacy, as Diller teaches it, includes a lot of togetherness for teacher and student. They read and write together so that the teacher can constantly triage the progress of both decoding and comprehending language.

“If we pay attention to children and know what we’re looking for, they’ll show us what to do next,” she explained.

My daughter was “lucky,” she explained, because the decoding of language was what she needed to take her developed oral language and get it onto the page. Her grasp of language comes easily, and phonics helps her access it in a new way, which excites her.

Other students, like Diller’s own daughter, don’t absorb phonics out of context. All the flashcards and rhymes in the world don’t help them turn code in to comprehension. They need simultaneous immersion in texts that engage them, Diller explained. She didn’t abandon flash cards, she integrated them into a broader literacy program for her daughter.

Teachers, Diller explained, have to be able to assess what is tripping up young readers, with comprehension being the ultimate goal.

It’s worth noting that Diller does not see a difference in income, gender, or anything else when it comes to learning to read. While vocabulary and oral language is typically more developed for higher income kids, Diller said, those children can still struggle to make the transition to writing and reading.

It does hold true, however, that interventions are key, and wealthier kids do have access to more options in that regard.

However, as one of the people who assists in those interventions, Diller maintains that “we’ve come a long way” in delivering and tracking the needed support inside classrooms.

Unfortunately, we’ve also dropped off on professional development, Diller said. In the late 1990s support for teachers’ continued learning was at a high. Now, she said, many teachers have to go find their own opportunities. Those that do, however, benefit greatly, and so do their students.

Diller was impressed with the teachers who attended the Pre-K 4 SA workshop. They were eager to learn and improve their craft, she said, and that bodes well for the kids in their classes.

Originally published as “Adventures in Literacy: Why your kid’s teacher needs professional development,” Hall Monitor, June 20, 2019

Read more:

- “[Hall Monitor] Meet The Gathering Place, One of San Antonio’s Newest and Busiest Charter Schools,” San Antonio Charter Moms, June 22, 2019

- “[Hall Monitor] The children still cannot read”: How I Became Convinced That Curriculum Is an Equity Issue,” San Antonio Charter Moms, June 15, 2019

- “[Hall Monitor] What We Talk About When We Talk About Safety and Discipline,” San Antonio Charter Moms, June 1, 2019

- “[Hall Monitor] Like Any Smart Person With a Messy Closet, SAISD Is Getting Help From Organizers,” San Antonio Charter Moms, May 25, 2019