Note from SA Charter Moms: We are proud to share guest posts from hallmonitor covering San Antonio’s public schools.

![[Hall Monitor] Texas Commission on Public School Finance: The Big Squeeze | San Antonio Charter Moms](https://sachartermoms.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/William_B_Travis_State_Office_Building_Austin_Texas_3-1024x768.jpg)

I have to be honest. I didn’t understand much of what was said at the April 5 Texas Commission on Public School Finance hearings.

Because I am not a tax accountant, I cannot take what I heard and make it blog-simple. My grasp on “discounted cashflow analysis” and “unfettered market valuation” is tenuous at best.

So I’m using this post to make some more human observations at the midpoint in scheduled hearings, which go until August.

After the commission’s first hearings, I said, probably cynically, that the chance of reform coming out of these meetings was slim. Up until now, the little flame of hope has been growing, in spite of the constant refrain of “spending doesn’t matter.” There seemed to be a consensus among most of the commission members that spending does matter somewhat or else they wouldn’t be there. There was solid testimony that with more money, the best things that schools are doing can be done more often.

“Tax day,” as I am calling the appropriately scheduled April hearings, was a stronger breeze against that flickering hope.

Observation One: Once Something Is broken, We Are Loath to Fix It

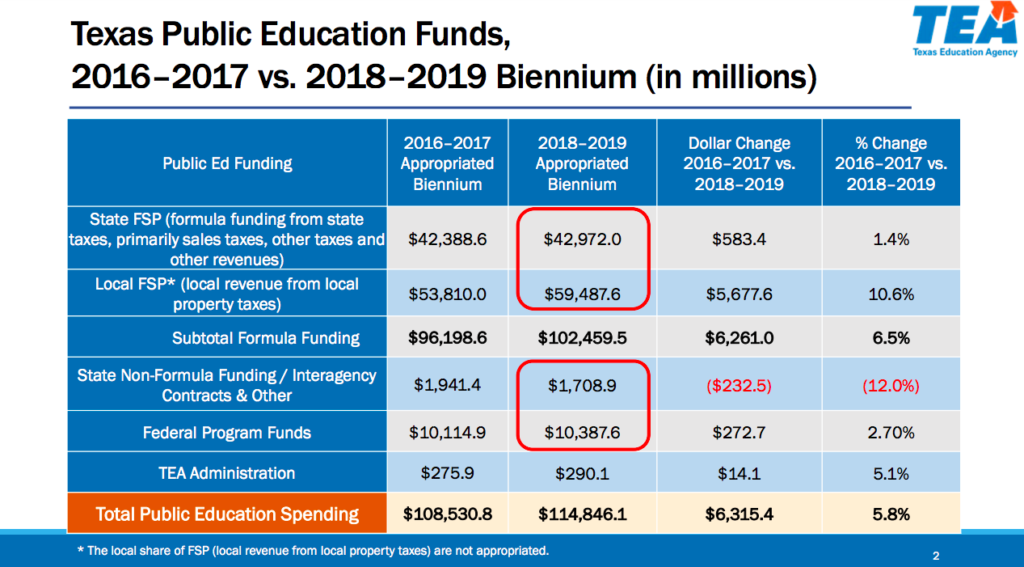

At one point, a discussion ensued on whether recapture funds should be considered part of the local share of school funding or the state share. This is sort of important, since increasing the state’s share of school funding is one of those pesky ideas that just keeps coming up. I say only “sort of” important because recapture is a relatively small portion of school funding.

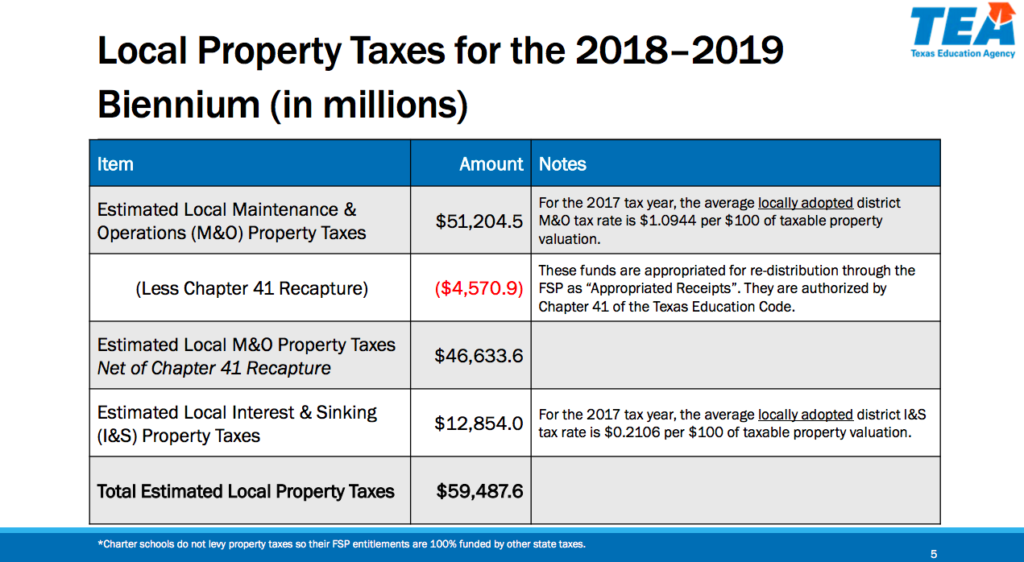

Right now, every time our property values go up, local tax revenue goes up. There’s a fixed number that a district gets from those property taxes. If property values go up so high that the district exceeds that fixed number, they send the excess to the state. This is recapture.

If districts don’t hit the fixed number through property taxes, the state kicks in the remainder, partially using the recaptured funds.

If the state committed to paying at least 50 percent of school funding no matter what, districts would feel the benefit of rising property values. Adjusting all the formulas would get very complicated, but that’s the basic argument. It has implications for recaptured funds as well.

The Texas Education Agency presented a chart that counted recaptured dollars as part of state funding. In March, the Legislative Budget Board (LBB) presented a chart that showed recapture funds as part of local funding. If the TEA presentation is right, the state has less ground to make up in reaching 50 percent of school funding. If that $50 million counts as local funds, at the LBB says, then the state has that much further to go to equalize its share of school funding.

Recaptured funds are considered a state appropriation, said Sen. Paul Bettencourt (R-Houston), literally throwing up his hands. “That’s what we’re stuck with.”

“Well no we’re not because we’re here to try and fix the system,” Rep. Dan Huberty (R-Humble) shot back.

Bettencourt acknowledged, that, oh yeah, the commission does have an ostensible purpose.

The little exchange shed a lot of light on how things work in Austin. It’s not a coincidence that so much of the testimony was provided by late-middle-aged white men who were openly defending the status quo on property taxes. If the current system works for you, then it’s terribly inconvenient to think that change might actually be an improvement.

Observation Two: We Have No Idea How Much Education Costs, or Should Cost, Only What We Don’t Want to Pay

At one point in the day, Texas’s former chief revenue estimator James LeBas recounted the long history of tax relief efforts by Legislatures past.

“They all went down in flames,” LeBas said. “We all wanted to cut property tax, but how were we going to pay for it? And that’s where things fell apart.”

That is, until 2006 when the Legislature successfully cut by one-third how much school districts were allowed to tax.

While LeBas admitted that the effects of the 2006 tax cut had been largely negated by other tax increases at the local level, he asked commissioners to imagine the nightmare scenario if the cuts had not been passed. Bettencourt described the cuts as a competitive maneuver to attract more businesses.

I had to wonder what was going through the mind of Pflugerville’s Doug Killian, the lone superintendent on the commission.

Ask any superintendent about the biggest screw to be turned on Texas schools in the 21st century, and they will tell you it was 2006 when their ability to raise local funds, and citizens’ ability to invest in their public schools, was cut by one-third.

The idea of local control did come up in the April 5 hearings as the most efficient way to balance the low tax/good school dilemma. In a Republican-controlled legislature that sounds like a viable idea, except that Texas’s legislature continues to see itself as Superman, swooping in to try to rescue citizens from the taxes they elect to pay. Governor Greg Abbott has vowed to resurrect the idea of local tax caps in 2019, after failing to pass such a bill in 2017.

Observation Three: In Texas, Students Are Expenditures and Businesses Are People

The commission devoted an entire panel to the effect that various tax policies might have on businesses and property owners. Representatives from Phillips 66 and Texas Instruments sat on the panel with smaller businesses and Habitat for Humanity.

Medium to large-sized businesses, it appears, feel that Texas has a “bias” against them, as TI’s William Blaylock put it. There was much hemming and hawing about how much of the tax burden does fall on businesses as opposed to homeowners. Was it 60 percent? Was it more?

The businesses didn’t come armed with policy recommendations, they simply made their case against raising property taxes on businesses. “We can live with the system we have,” Blaylock said.

When the topic of split tax rolls (designed to give homeowners a break and ask more from business) came up, LeBas said, “Business just want to be treated like everybody else.”

Now, there are real concerns about taxing businesses too heavily, especially small businesses. However, commission member Todd Williams of Dallas raised a critical point: businesses have concerns beyond taxes.

“It’s not just about being the lowest cost, it’s also about having an educated workforce,” Williams said.

Unless you are still holding onto trickle-down economics (along with your crimped hair and Hammer pants), making it easy for businesses to move to a state with low educational attainment is not an “everybody wins” proposition.

Right now Texas has a 3.9 percent unemployment rate . . . and a 15–17 percent poverty rate (depending on how you measure). That means that you can have a job, and still not be able to feed your family without government assistance. Those “good jobs,” the ones at Texas Instruments, require a college degree. And to get one of those, your high school has to get you college ready.

Conclusion

I don’t want to make it seem as though there was no productive discussion about how to generate more funding out of current revenue streams. Nor do I want to minimize the importance of tax rates when it comes to affordable housing. Closing loopholes, reforming the appraisal process, and several other viable solutions were proposed, that would—in theory—remedy some of the burden on homeowners, and squeeze a little more out for public schools.

However, as commission chair Judge Scott Brister was quick to remind us, for every squeeze there must be an equal and opposite re-squeeze.

“We’re gonna have a squeeze of what we can afford to spend on,” Brister said, after reading a list of expenditures Texans had submitted to the commission via email. Expenditures like special education, teacher healthcare, gifted and talented programming.

Brister reminded the commission that at some point there would have to be a discussion of how to get more out of the funds that are already there. “We heard from districts that are doing that,” he said.

I don’t know what Brister hears and doesn’t hear at these things. They are long, and tuning out here and there would be understandable. However, I’ve heard the same good ideas from Dallas ISD, San Antonio ISD, Lubbock ISD, Pharr-San Juan-Alamo ISD, and so many more. What I haven’t heard is ANY of them saying that they are going to be able to continue those excellent services at current funding levels. Unlike our friends at Texas Instruments, they cannot make do with the system as is.

Originally published as “Texas Commission on Public School Finance: The Big Squeeze,” Hall Monitor, April 6, 2018

Read more:

- “[Hall Monitor] Texas Commission on Public School Finance: The Road to Byzantium,” San Antonio Charter Moms, March 29, 2018

- “[Hall Monitor] Texas Commission on Public School Finance: Time Is Money . . . and Some Kids Don’t Have Either,” San Antonio Charter Moms, March 21, 2018

- “[Hall Monitor] Texas School Finance Commission: You Get the Teacher You Pay For,” San Antonio Charter Moms, March 16, 2018

- “[Hall Monitor] Texas School Finance Commission: Rough Equity,” San Antonio Charter Moms, March 15, 2018

![[Hall Monitor] Texas Commission on Public School Finance: The Big Squeeze | San Antonio Charter Moms [Hall Monitor] Texas Commission on Public School Finance: The Big Squeeze | San Antonio Charter Moms](https://sachartermoms.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/William_B_Travis_State_Office_Building_Austin_Texas_3.jpg)