The West Starts Here with the Briscoe Western Art Museum

Although San Antonio’s claim to fame is the Battle of the Alamo, and the historic site that centers a community shaped by Spanish and Mexican cultures, let’s remember that San Antonio was also one of the cities most vital to the success of the American cattle trade. That’s why, at the Briscoe Western Art Museum, we say, “The West Starts Here.” Here is a round up of activities to help you and your kids learn about San Antonio’s role in shaping the art and culture of the West.

For more ideas about summer experiences you can do while learning at home with your kids, visit the main page, Charter a Summer of Learning.

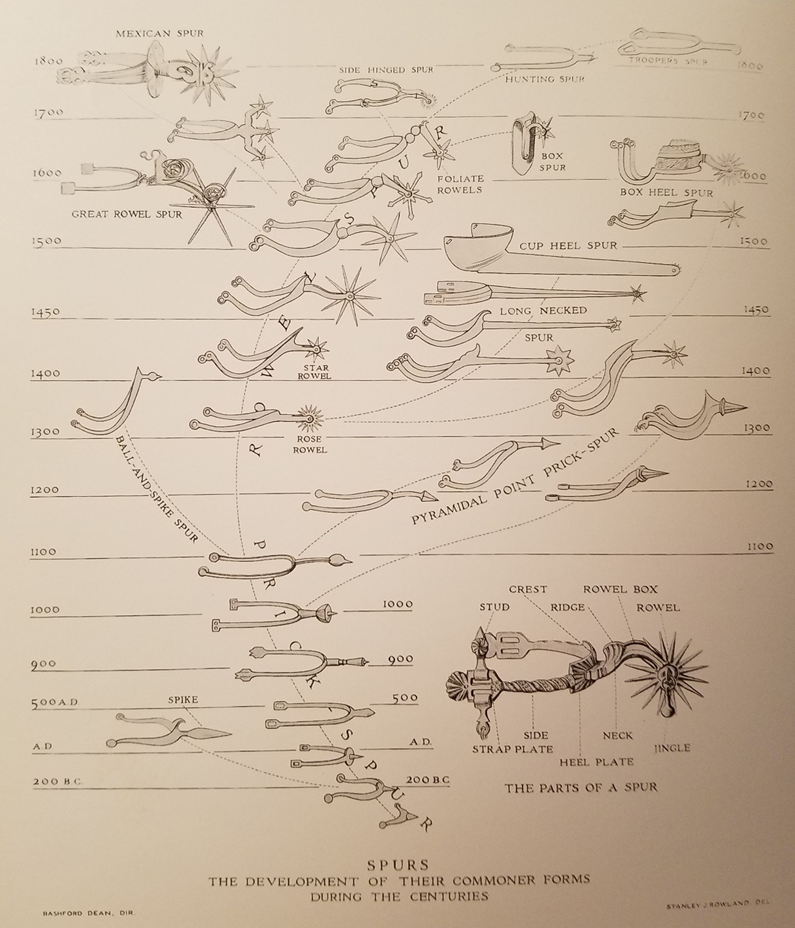

From Spurs to Barbed Wire

The story of cattle drives in South Texas goes back to the time of Spanish settlement. Native people living in the Franciscan Missions spent part of their days learning how to ride horses and wrangle cattle, which were used for their meat, hides, and tallow (i.e., fat, which was made into candles, etc.). In spite of the fact that many Native people had never used or seen horses prior to the arrival of the Spanish, they were quick learners and rapidly mastered the skills developed by Spanish vaqueros. Eventually, Franciscan missionaries even commissioned special spurs for Native vaqueros to use, with features that allowed them to be worn with moccasins. Here is an example of one of these spurs from the collection of the Briscoe Western Art Museum.

Spanish vaqueros had mastered horsemanship, roping, and animal husbandry in Europe, and found the plains of Northern Mexico and South Texas ideal locations to establish herds of hearty Iberian livestock, that were turned out to graze. Many of these animals lived feral for months or even years at a time, adapting to the climate and landscape of South Texas until thousands ran wild along the Rio Grande. These herds would evolve into the Texas longhorn cattle, easily identified by their impressive horns.

While many ran wild, those that remained constituted a major part of Tejano livelihood. In fact, Texas cattle, driven from San Antonio, were also used to feed hungry soldiers during the American Revolution and miners during the California Gold Rush. One of the museum’s signature pieces along the Riverwalk, “Camino de Galvez” by Texan sculptor T.D. Kelsey, illustrates the first cattle drive from Texas to the American colonies.

T.D. Kelsey, “Camino De Galvez”, bronze, 126″ x 155″ x 84”, Purchased with funds provided by the Jack and Valerie Guenther Foundation in honor of Lindsay and Jack Guenther, Jr. Family.

After the close of the Civil War, cattle-rich and cash-poor Texans looked for ways to recover from economic devastation. The solution to their problems came in the form of the hundreds of thousands of wild longhorn cattle roaming across South Texas and Northern Mexico. Their ready availability made the Texas traildriving cattle industry possible, as it had in 1779. As those herds began their drive northward, they stopped in San Antonio to supply themselves for the months on the trail ahead, proving yet again that “The West Starts Here.” Oftentimes the outfit’s chuckwagon would park in Alamo Plaza as the necessary supplies were acquired for the toilsome months ahead.

From these months on the trail, the Texas cowboy become a Western icon due to their skill on horseback, wild spirit, and ability to endure hardship. They were celebrated in Western “Dime Novels”: books on cowboy life were some of the most popular publications of the late 19th and early 20th century. The cowboys were masters of the open range, until the invention of barbed wire.

Ragan Gennusa, “Out of the Brush,” Oil on canvas, 20″ x 40”, Briscoe Western Art Museum, Night of Artists Purchase 2016

The reaction to Joseph Gidden’s invention of light-weight, inexpensive fencing is often credited as the object that “tamed the West.” With the mass-production of this hardware, individual ranchers were able to delineate their property lines with relative ease. People praised the quality of barbed wire as “it takes no room, exhausts no soil, shades no vegetation, is proof against high winds, makes no snowdrifts, and is both durable and cheap.” This singular invention was originally looked upon as being too flimsy to really hold cattle, until it was successfully demonstrated by John Warne Gates in downtown San Antonio—more proof that the west starts here.

So remember, as you teach your children about the Spanish Missions, El Camino Real, or Davy Crockett at the Alamo, also teach them about the San Antonio’s role as the gateway to the western cattle trails. Below you will find some interactive activities and links to bring customs and culture of cowboys, cowgirls and vaqueros to life.

Western Wear for Young Children: Make a Cowboy Vest

Little ones learning to color and use scissors can make themselves a cowboy vest. Take a large brown paper grocery bag—the ones from Trader Joe’s or Whole Foods are perfect. Here are the steps:

Turn the bag upside down (and inside out if you would like to use the blank brown paper).

Cut one slit from the top (now the bottom) of the bag up to the flat bottom (now the top).

Cut a head and two arm holes according to what will fit your child.

Let your child decorate their Western vest with crayons, fringe, or whatever else they would like.

Western Gear for Middle-Grade Children: Making a Cowboy Spur

Spurs were a vital part of the cowboy’s equipment. Most people notice the spurs, the way they jingle and spin. For your grade schoolers, I recommend making a pinwheel; the shape and spinning motion of the pinwheel mimic the spin of the rowel. The best instructional video I have found on how to make a pinwheel is from the Make Kids Crafts channel:

Once you have made the pinwheel, decorated, and played with it a bit, you could move into a discussion on cowboy spurs.

Source: Ned and Jody Martin, “Bit and Spur Makers in the Vaquero Tradition: A Historical Perspective,” Hawk Hill Press, 1997, at p. 46.

Spurs themselves are thousands of years old. They have evolved radically over the years and, for the cowboys, you could often tell where a cowboy was from by the style of spurs he wore. The cowboy styles of spurs that we have come to know have largely originated in Mexico and evolved to fit the needs of the regions where the cowboys worked and what they wanted from their spurs. Below you will see three different styles of spurs: Texan, Vaquero (from California), and Buckaroo (from up north around Idaho, Wyoming and Nevada).

Texan: Texan spurs typically had a short “shank,” small, blunt rowels, and wide heelbands. They were similar in construction to some Northern Mexican spurs, though they were not as intricate, made of iron instead of Mexican silver and were often designed for utility over show. Below is a special kind of spur, called the OK Spur. This was made out of a single piece of iron, making it strong, flexible and was relatively inexpensive; at only 50 cents a pair they were a great buy for a poor cowboy

Vaquero: The vaquero spurs were the most like the beautiful Mexican spurs in their construction, with their use of silver inlays and large rowels. They were useful, though especially designed for show and often featured heel chains and jingle-bobs to add a little sound to when they would walk around or ride by.

Buckaroo: The northern buckaroo spurs appeared to be a mix of the vaquero and Texan styles. They often have smaller rowels, but longer, curved shanks and a chap guards. They also normally had large leather straps to fix the spurs to their boots, with large silver concho-style buttons.

The West Starts Here . . . with a Cowboy Breakfast

For this activity, older students will be allowed to stretch their skills a bit by doing some Dutch-oven cooking. Cooking with cast iron has been part of cattle culture from the beginning, as the camp cook would prepare meals for the hungry cowboys, using the “chuckwagon” as a mobile kitchen. Some of the foods prepared were biscuits, bacon, gravy, and coffee. To give these kids a bit of the chuckwagon experience, I recommend preparing Dutch-oven biscuits and bacon gravy.

Watch this video from chuckwagon cook Ed Parsons:

Chuckwagon Cooking with Ed Parsons – Briscoe Western Art Museum from Briscoe Western Art Museum on Vimeo.

Biscuit preparation: You can, if you are looking for a quick biscuit, purchase the refrigerated Pillsbury biscuits and arrange them about two inches apart in a cast iron Dutch-oven, and bake as directed in a conventional oven.

Alternatively, if your family has a favorite biscuit recipe, either work with your student to make them from scratch or coordinate a Zoom meeting with a grandparent or other relative where your child have a virtual cooking session, and learn about family cooking traditions as well.

Bacon preparation: I find thick sliced bacon works best and is incredibly flavorful when cooked in a cast-iron skillet. Thicker bacon also tends to leave behind more drippings for your gravy. Cook to your preference; parental supervision recommended.

Gravy Preparation: The gravy is a simple addition of milk and flour to the bacon drippings. It can splatter a bit, so be careful. I tried “Bacon Gravy for Biscuits” by Nikki Lakey and found it quite tasty.

After you have made all the components, combine and enjoy! Once you have everything ready, your child’s homework/breakfast will make an excellent segue into a lesson about cowboy life and culture in South Texas, and how “The West Starts Here.”

At-Home Learning with the Briscoe Western Art Museum

The Briscoe Western Art Museum’s mission is to preserve the art, culture, and history of the West. Our collection includes objects and artifacts that tell the story of the North American cattle trade, vaqueros, cowgirls, and cowboys. Online, Beyond the Briscoe content has more activities for at-home learning, including these printable coloring pages featuring Western art:

Logan Maxwell Hagege, “A Day in the West”

More Resources to Learn About How “The West Starts Here”

“The Bar J Wranglers: Cowboy Music from Wyoming,” Library of Congress—The Bar J Wranglers singing traditional Cowboy Songs

“Vaqueros and Cowboys,” Texas Parks & Wildlife—Historical information on cowboys, vaqueros, and cattle drives

“Cowboy Coffee”—Cowboy Mark teaches kids how to make cowboy coffee for their parents

“The Cowboy’s Horse,” National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, Oklahoma City—Learn about how valuable the horse was, and is, to the cowboy

Charter Moms Chats

Watch Inga Cotton’s interview with Ryan Badger on Charter Moms Chats.

For more ideas about summer experiences you can do while learning at home with your kids, visit the main page, Charter a Summer of Learning.

About the Author

Ryan Badger is the Curator of Collections with the Briscoe Western Art Museum. He has worked as a public historian for the past ten years, throughout the Western U.S., and in Washington D.C. at the Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian. His real passion is bringing Western stories to life for the public and his two children, who are regularly his guinea-pigs whenever he is preparing a new tour or program. In his downtime, he enjoys exploring wild places where he can socially distance and admire the beauty of the wilderness; when that is not possible, he also enjoys reading and leatherwork—making wallets for people that do not need any more wallets.

One Comment